The 3 Essential Steps Before Starting to Resolve Incidents

Turn Chaos into Structured and Predictable Incident Management

If managing incidents on its own can be stressful, imagine doing it without any organization.

Depending on the volume of incoming requests and their severity, chaos can quickly take over. From having no visibility into the number of requests hitting the incident response teams, to being unaware of the biggest problem hotspots, or even having technicians resolving non-urgent, low-impact issues while critical ones sit in the queue.

Follow these steps to make your day-to-day operations smoother.

Steps in Incident Management

There are three essential minimum steps for proper incident management.

Step 1: Log the Incident

The first step every technician must be instructed on is that an incident does not exist unless it is logged. For that, the ideal scenario is to have a ticketing platform that users are familiar with - everyone should receive training on it when it is implemented, and it should also be part of the onboarding training plan for new employees.

I won’t go into the topic of who should open the ticket, but in case you define it should be the user, be careful with agents who kindly open tickets on behalf of users - these cases are easy to notice in day-to-day operations, but the manager should regularly review the platform’s statistics to understand the scale of the problem. These “kind gestures” can undermine years of user education aimed at getting them to open tickets instead of approaching technicians directly.

If users have other communication channels to reach technicians and can initiate incident reporting that way, I still maintain that the incident must be logged - therefore someone has to create the ticket. In this case, it should be the technicians. The biggest challenge is getting technicians to create the ticket before starting the analysis and resolving the issue, so they don’t forget or get lazy to do it later.

In both scenarios, in less mature teams, it is common to see numerous issues solved without a ticket. This means that at the end of the day (or at the end of the month or year in accumulation), the statistics will not reflect the actual number of incidents that occurred, the real Mean Time to Resolve (MTTR), the number of incidents by category, nor the hours the team truly dedicated to this area.

Step 2: Categorize the Incident

Once logged, the incident must be categorized. Categorization helps assign the incident to the appropriate support team and also allows reporting to show which categories are becoming the most problematic.

Creating categories in a support tool is something that should be carefully considered and, like everything else, should evolve over time. What I mean by this is that it’s normal to have doubts about the structure you’re going to implement - whether it should have two levels (category and subcategory) or three (category, subcategory, and item), whether it should be specific enough to include modules within a particular application, or kept more generic.

There is no single “correct” way to implement categories. Each organization should think about what works best for them. However, based on my experience, the trend has been to simplify - meaning simplify both for users and for technicians. But only by analyzing the data can you properly assess whether this simplification limits management’s ability to understand where most problems are occurring, or where the most critical issues for the organization lie, and where time should be invested to address them.

Step 3: Prioritize the Incident

Once the incident is categorized, its priority must be defined among all the other unresolved tickets.

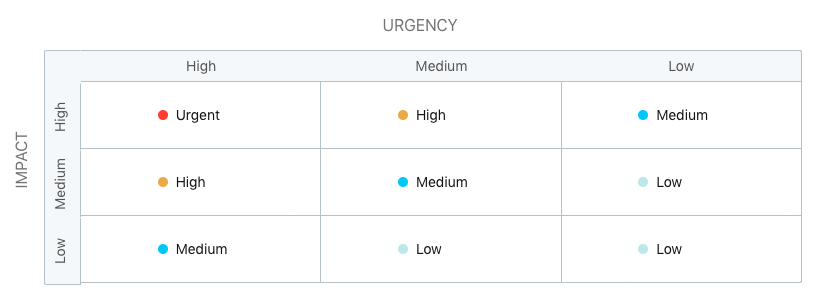

The priority of a ticket is determined by impact vs. urgency. This means there should be a scale for impact, another for urgency, and a matrix that clearly indicates the priority based on these two variables.

Personally, I like using the matrix provided by Freshservice (this is an affiliate link - if you sign up, I may earn a small commission at no additional cost to you):

On the X-axis we have urgency, and on the Y-axis we have impact. By classifying both, we obtain the priority that should be assigned to the ticket.

Of course, even after defining the priority, it may still match the priority of other incidents awaiting resolution. That’s where experience and business knowledge come into play.

Technicians with more years in the organization will intuitively know which tickets should take precedence - it will vary from case to case, but having alignment with leadership is ideal.

Less experienced technicians should rely on their colleagues or, ideally, their manager to understand which issues they should tackle first.

Conclusion

Incident Management only works when the fundamentals are in place: every incident must be logged, properly categorized, and prioritized based on impact and urgency. These practices may seem simple, but they form the backbone of an efficient and mature support organization.

By applying these three steps consistently, teams gain clearer visibility of their workload, reduce resolution times, improve communication with users, and build a reliable dataset to support better decision-making.

Improving Incident Management is a continuous journey - not a one-time project. Start with the basics, adapt the process to your organization, and refine it over time. Small improvements, applied consistently, lead to meaningful long-term results.

If you already follow these practices or have additional recommendations, feel free to share your experience in the comments.